This post is part of our blog series “Scholars Speak,” which features writing from our 2025 cohort of Preservation Scholars. Click the link to learn more about this donor-funded program that aims to increase the breadth of voices in the Texas historical narrative by placing students from underrepresented cultural and ethnic backgrounds in paid, 10-week long summer internship positions at the Texas Historical Commission.

Scholars Speak: El Barrio Laredito—a Lesser Known Story from San Antonio

While researching undertold historical markers in Texas, I came across the often-overlooked story of a San Antonio neighborhood whose Hispanic roots stretch back nearly 300 years. Both San Antonio natives and tourists are likely familiar with downtown landmarks such as El Mercado, San Fernando Cathedral, and the Spanish Governor’s Palace, all of which are within walking distance of each other. What is less commonly discussed, however, is the cultural history that surrounds these sites—and the predominantly Spanish-speaking neighborhood that thrived there for centuries.

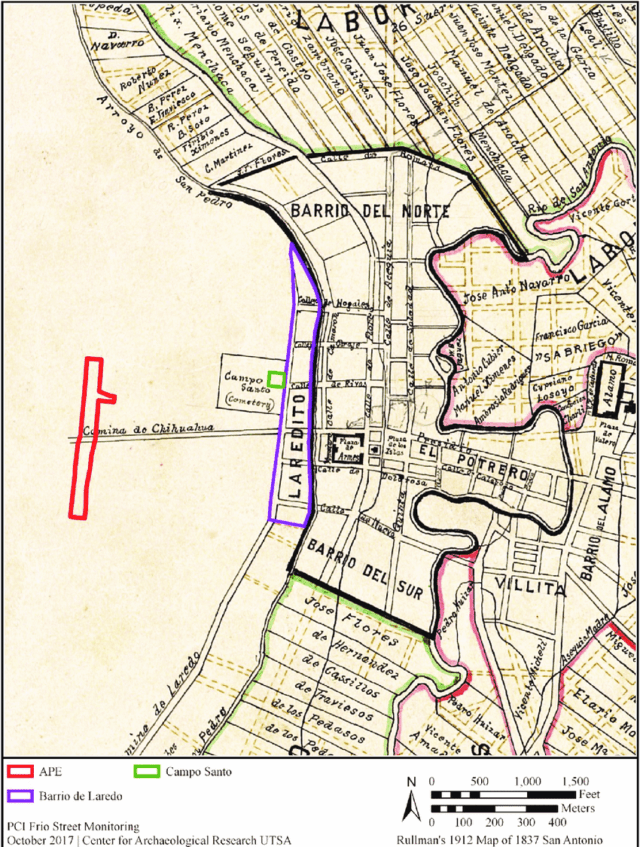

If you walk along the south side of the bridge where Dolores Street crosses over San Pedro Creek, you might notice a panel detailing the history of El Barrio Laredito. It briefly explores the history of the neighborhood, which emerged as a hub for Hispanic culture and daily life as early as the mid-18th century. A map from 1764 depicted the area just west of the San Antonio River, where trade routes crossed San Pedro Creek into the Spanish military fort, Presidio de San Antonio de Béxar. By 1812, maps of the same area included the Military Plaza, San Fernando Cathedral, and a settlement labeled “Laredito,” home to many presidio families of mestizo heritage. As commerce expanded, and Mexico gained independence from Spain, Laredito grew into a vibrant center of Mexican American culture.

Following the establishment of the Republic of Texas, the influx of Anglo Americans into San Antonio made Laredito a more centralized enclave for an increasingly marginalized Hispanic population. During this period, a prominent political figure and resident of Laredito, José Antonio Navarro, began advocating for the rights of Tejanos. In the 1880s, entrepreneurial women known as the Chili Queens served traditional foods in the open-air Military Plaza, while spaces like Plaza del Zacate (now Milam Park) and El Mercado became popular cultural gathering spots in Laredito. The neighborhood also played a role in labor activism; in the 1930s, the exploitation of predominantly Hispanic pecan shellers inspired Laredito resident Emma Tenayuca to organize protests in the Military Plaza demanding better working conditions.

The story of El Barrio Laredito is largely overlooked in the broader historical narrative of San Antonio. Much of the neighborhood’s physical structure was lost during a wave of urban renewal projects that reshaped the downtown area in the 1960s. Nevertheless, the area’s deep roots in Hispanic culture are maintained through the traditions of Laredito’s descendants, reflected in its food, music, celebrations, and a handful of remaining landmarks such as Casa Navarro State Historic Site, Historic Market Square, Military Plaza, and the Alameda Theater. In June, I was able to visit San Antonio and scout out these locations. Although I had been to the downtown area before, exploring the same streets with images of its centuries-long history as a backdrop inspired a renewed sense of wonder and curiosity. Both are driving factors for me in my journey toward a career in preservation.